Open source sustainability has been nothing short of an oxymoron. Engineers around the world pour their sweat and frankly, their hearts into these passion projects that undergird all software in the modern internet economy. In exchange, they ask for nothing in return except for recognition and help in keeping their projects alive and improving them. It’s an incredible movement of decentralized voluntarism and represents humanity at its best.

The internet and computing giants — the heaviest users of open source in the world — are collectively worth trillions of dollars, but you would be remiss in thinking that their wealth has somehow trickled down to the maintainers of the open source projects that power them. Working day jobs, maintainers today can struggle to find the time to fix critical bugs, all the while facing incessant demands from users requesting free support on GitHub. Maintainer burnout is a monstrous challenge.

That distressing situation was chronicled almost exactly two years ago by Nadia Eghbal, in a landmark report on the state of open source published by the Ford Foundation. Comparing open source infrastructure to “roads and bridges,” Eghbal provided not just a comprehensive overview of the challenges facing open source, but also a call-to-arms for more users of open source to care about its economics, and ultimately, how these critical projects can sustain themselves indefinitely.

Two years later, a new crop of entrepreneurs, open source maintainers, and organizations have taken Eghbal up on that challenge, developing solutions that maintain the volunteer spirit at the heart of open source while inventing new economic models to make the work sustainable. All are early, and their long-term effects on the output and quality of open source are unknown. But each solution offers an avenue that could radically change the way we think of a career in open source in the future.

No one sees that the Roads and Bridges are falling down

Eghbal’s report two years ago summarized the vast issues facing open source maintainers, challenges that have remained essentially unchanged in the interim. It’s a quintessential example of the “tragedy of the commons.” As Edghbal wrote at the time, “Fundamentally, digital infrastructure has a free rider problem. Resources are offered for free, and everybody (whether individual developer or large software company) uses them, so nobody is incentivized to contribute back, figuring that somebody else will step in.” That has led to a brittle ecosystem, just as open source software reached the zenith of its influence.

The challenges, though, go deeper. It’s not just that people are free riding, it’s often that they don’t even realize it. Software engineers can easily forget just how much craftsmanship has gone into the open source code that powers the most basic of applications. NPM, the company that powers the module repository for the Node ecosystem, has nearly 700,000 projects listed on its registry. Starting a new React app recently, NPM installed 1105 libraries with my initial project in just a handful of seconds. What are all of these projects?

And more importantly, who are all the people behind them? That dependency tree of libraries abstracts all the people whose work has made those libraries available and functional in the first place. That black box can make it difficult to see that there are far fewer maintainers working behind the scenes at each of these open source projects than what one might expect, and that those maintainers may be struggling to work on those libraries due to lack of funding.

Eghbal pointed to OpenSSL as an example, a library that powers a majority of encrypted communications on the web. Following the release of the Heartbleed security bug, people were surprised to learn that the OpenSSL project was the work of a very small team of individuals, with only one of them working on it full-time (and at a very limited salary compared to industry norms).

Such a situation isn’t unusual. Open source projects often have many contributors, but only a handful of individuals are truly driving a particular project forward. Lose that singular force either to burnout or distraction, and a project can be adrift quickly.

When free isn’t free

No one wants open source to disappear, or for maintainers to burnout. Yet, there is a strong cultural force against commercial interests in the community. Money is corrupting, and dampens the voluntary spirit of open source efforts. More pragmatically, there are vast logistical challenges with managing money on globally distributed volunteer teams that can make paying for work logistically challenging.

Unsurprisingly, the vanguard of open source sustainability sees things very differently. Kyle Mitchell, a lawyer by trade and founder of License Zero, says that there is an assumption that “Open source will continue to fall from the sky like manna from heaven and that the people behind it can be abstracted away.” He concludes: “It is just really wrong.”

That view was echoed by Henry Zhu, who is the maintainer of the popular JavaScript compiler Babel. “We trust startups with millions of VC money and encourage a culture of ‘failing fast,’ yet somehow the idea of giving to volunteers who may have showed years of dedication is undesirable?” he said.

Xavier Damman, the founder and CEO of Open Collective, says that “In every community, there are always going to be extremists. I hear them and understand them, and in an ideal world, we all have universal basic income, and I would agree with them.” Yet, the world hasn’t moved to such an income model, and so supporting the work of open source has to be an option. “Not everyone has to raise money for the open source community, but the people who want to, should be able to and we want to work with them,” he said.

Mitchell believes that one of the most important challenges is just getting comfortable talking about money. “Money feels dirty until it doesn’t,” he said. “I would like to see more money responsibility in the community.” One challenge he notes is that “learning to be a great maintainer doesn’t teach you how to be a great open source contractor or consultant.” GitHub works great as a code repository service, but ultimately doesn’t teach maintainers the economics of their work.

Supporting the individual contributor: Patreon and License Zero

Perhaps the greatest debate in sustaining open source is deciding who or what to target: the individual contributors — who often move between multiple projects — or a particular library itself.

Take Feross Aboukhadijeh for example. Aboukhadijeh (who, full disclosure, was once my college roommate at Stanford almost a decade ago) has become a major force in the open source world, particularly in the Node ecosystem. He served an elected term on the board of directors of the Node.js Foundation, and has published 125 repositories on GitHub, including popular projects like WebTorrent (with 17,000 stars) and Standard (18,300 stars).

Aboukhadijeh was looking for a way to spend more time on open source, but didn’t want to be beholden to working on a single project or writing code at a private company that would never see the light of day. So he turned to Patreon as a means of support.

(Disclosure: CRV, my most immediate former employer, is the series A investor in Patreon. I have no active or passive financial interest in this specific company. As per my ethics statement, I do not write about CRV’s portfolio companies, but given that this essay focuses on open source, I made an exception).

Patreon is a crowdsourced subscription platform, perhaps best known for the creatives it hosts. These days though, it is also increasingly being used by notable open source contributors as a way to connect with fans and sustain their work. Aboukhadijeh launched his page after seeing others doing it. “A bunch of people were starting up Patreons, which was kind of a meme in my JavaScript circles,” he said. His Patreon page today has 72 contributors providing him with $2,874 in funding per month ($34,488 annually).

That may seem a bit paltry, but he explained to me that he also supplements his Patreon with funding from organizations as diverse as Brave (an adblocking browser with a utility token model) to PopChest (a decentralized video sharing platform). That nets him a couple of more thousands of dollars per month.

Aboukhadijeh said that Twitter played an outsized role in building out his revenue stream. “Twitter is the most important on where the developers talk about stuff and where conversations happen…,” he said. “The people who have been successful on Patreon in the same cohort [as me] who tweet a lot did really well.”

For those who hit it big, the revenues can be outsized. Evan You, who created the popular JavaScript frontend library Vue.js, has reached $15,206 in monthly earnings ($182,472 a year) from 231 patrons. The number of patrons has grown consistently since starting his Patreon in March 2016 according to Graphtreon, although earnings have gone up and down over time.

Aboukhadijeh noted that one major benefit was that he had ownership over his own funds. “I am glad I did a Patreon because the money is mine,” he said.

While Patreon is one direct approach for generating revenues from users, another one is to offer dual licenses, one free and one commercial. That’s the model of License Zero, which Kyle Mitchell propsosed last year. He explained to me that “License Zero is the answer to a really simple question with no simple answers: how do we make open source business models open to individuals?”

Mitchell is a rare breed: a lifelong coder who decided to go to law school. Growing up, he wanted to use software he found on the web, but “if it wasn’t free, I couldn’t download it as a kid,” he said. “That led me into some of the intellectual property issues that paved a dark road to the law.”

License Zero is a permissive license based on the two-clause BSD license, but adds terms requiring commercial users to pay for a commercial license after 90 days, allowing companies to try a project before purchasing it. If other licenses aren’t available for purchase (say, because a maintainer is no longer involved), then the language is no longer enforceable and the software is offered as fully open source. The idea is that other open source users can always use the software for free, but for-profit uses would require a payment.

Mitchell believes that this is the right approach for individuals looking to sustain their efforts in open source. “The most important thing is the time budget – a lot of open source companies or people who have an open source project get their money from services,” he said. The problem is that services are exclusive to a company, and takes time away from making a project as good as it can be. “When moneymaking time is not time spent on open source, then it competes with open source,” he said.

License Zero is certainly a cultural leap away from the notion that open source should be free in cost to all users. Mitchell notes though that “companies pay for software all the time, and they sometimes pay even when they could get it for free.” Companies care about proper licensing, and that becomes the leverage to gain revenue while still maintaining the openness and spirit of open source software. It also doesn’t force open source maintainers to take away critical functionality — say a management dashboard or scaling features — to force a sale.

Changing the license of existing projects can be challenging, so the model would probably best be used by new projects. Nonetheless, it offers a potential complement or substitute to Patreon and other subscription platforms for individual open source contributors to find sustainable ways to engage in the community full-time while still putting a roof over their heads.

Supporting the organization: Tidelift and Open Collective

Supporting individuals makes a lot of sense, but often companies want to support the specific projects and ecosystems that underpin their software. Doing so can be next to impossible. There are complicated logistics required in order for companies to fund open source, such as actually having an organization to send money to (and for many, to convince the IRS that the organization is actually a non-profit). Tidelift and Open Collective are two different ways to open up those channels.

Tidelift is the brainchild of four open-source fanatics led by Donald Fischer. Fischer, who is CEO, is a former venture investor at General Catalyst and Greylock as well as a long-time executive at Red Hat. In his most recent work, Fischer invested in companies at the heart of open source ecosystems, such as Anaconda (which focuses on scientific and statistical computing within Python), Julia Computing (focused on the Julia programming language), Ionic (a cross-platform mobile development framework), and TypeSafe now Lightbend (which is behind the Scala programming language).

Fischer and his team wanted to create a platform that would allow open source ecosystems to sustain themselves. “We felt frustrated at some level that while open source has taken over a huge portion of software, a lot of the creators of open source have not been able to capture a lot of the value they are creating,” he explained.

Tidelift is designed to offer assurances “around areas like security, licensing, and maintenance of software,” Fischer explained. The idea has its genesis in Red Hat, which commercialized Linux. The idea is that companies are willing to pay for open source when they can receive guarantees around issues like critical vulnerabilities and long-term support. In addition, Tidelift handles the mundane tasks of setting up open source for commercialization such as handling licensing issues.

Fischer sees a mutualism between companies buying Tidelift and the projects the startup works with. “We are trying to make open source better for everyone involved, and that includes both the creators and users of open source,” he said. “What we focus on is getting these issues resolved in the upstream open source project.” Companies are buying assurances, but not exclusivity, so if a vulnerability is detected for instance, it will be fixed for everyone.

Tidelift initially launched in the JavaScript ecosystem around React, Angular, and Vue.js, but will expand to more communities over time. The company has raised $15 million in venture capital from General Catalyst and Foundry Group, plus former Red Hat chairman and CEO Matthew Szulik.

Fischer hopes that the company can change the economics for open source contributors. He wants the community to move from a model of “get by and survive” with a “subsistence level of earnings” and instead, help maintainers of great software “win big and be financially rewarded for that in a significant way.”

Where Tidelift is focused on commercialization and software guarantees, Open Collective wants to open source the monetization of open source itself.

Open Collective is a non-profit platform that provides tools to “collectives” to receive money while also offering mechanisms to allow the members of those collectives to spend their money in a democratic and transparent way.

Take, for instance, the open collective sponsoring Babel. Babel today receives an annual budget of $113,061 from contributors. Even more interesting though is that anyone can view how the collective spends its money. Babel currently has $28,976.82 in its account, and every expense is listed. For instance, core maintainer Henry Zhu, who we met earlier in this essay, expensed $427.18 on June 2nd for two weeks worth of Lyft rides in SF and Seattle.

Xavier Damman, CEO and founder of Open Collective, believes that this radical transparency could reshape how the economics of open source are considered by its participants. Damman likens Open Collective to the “View Source” feature of a web browser that allows users to read a website’s code. “Our goal as a platform is to be as transparent as possible,” he said.

Damman was formerly the founder of Storify. Back then, he built an open source project designed to help journalists accept anonymous tips, which received a grant. The problem was that “I got a grant, and I didn’t know what to do with the money.” He thought of giving it to some other open source projects, but “technically, it was just impossible.” Without legal entities or paperwork, the money just wasn’t fungible.

Open Collective is designed to solve those problems. Open Collective itself is a 501(c)6 non-profit, and it technically receives all money destined for any of the collectives hosted on its platform as their fiscal sponsor. That allows the organization to send out invoices to companies, providing them with the documentation they need in order to write a check. “As long as they have an invoice, they are covered,” Damman explained.

Once a project has money, it is up to the maintainers of that community to decide how to spend it. “It is up to each community to define their own rules,” Damman said. He notes that open source contributors can often spend the money on the kind of uninteresting work that doesn’t normally get done, which Damman analogized as “pay people to keep the place clean.” No one wants to clean a public park, but if no one does it, then no one will ever use the park. He also noted that in-person meetings are a popular usage of revenues.

Open Collective was launched in late 2015, and since then has become home to 647 open source projects. So far, Webpack, the popular JavaScript build tool, has generated the most revenue, currently sitting at $317,188 a year. One major objective of the non-profit is to encourage more for-profit companies to commit dollars to open source. Open Collective places the logos of major donors on each collective page, giving them visible credit for their commitment to open source.

Damman’s ultimate dream is to change the notion of ownership itself. We can move from “Competition to collaboration, but also ownership to commons,” he envisioned.

Sustaining sustainability

It’s unfortunately very early days for open source sustainability. While Patreon, License Zero, Tidelift, and Open Collective are different approaches to providing the infrastructure for sustainability, ultimately someone has to pay to make all that infrastructure useful. There are only a handful of Patreons that could substitute for an engineer’s day job, and only two collectives by my count on Open Collective that could support even a single maintainer full time. License Zero and Tidelift are too new to know how they will perform yet.

Ultimately though, we need to change the culture toward sustainability. Henry Zhu of Babel commented, “The culture of our community should be one that gives back and supports community projects with all that they can: whether with employee time or funding. Instead of just embracing the consumption of open source and ignoring the cost, we should take responsibility for it’s sustainability.”

In some ways, we are merely back to the original free rider problem in the tragedy of the commons — someone, somewhere has to pay, but all get to share in the benefits.

The change though can happen through all of us who work on code — every software engineer and product manager. If you work at a for-profit company, take the lead in finding a way to support the code that allows you to do your job so efficiently. The decentralization and volunteer spirit of the open source community needs exactly the same kind of decentralized spirit in every financial contributor. Sustainability is each of our jo

from iFeeltech IT News Mix4 https://techcrunch.com/2018/06/23/open-source-sustainability/

from iFeeltech, INC https://ifeeltechinc.wordpress.com/2018/06/23/open-source-sustainability/

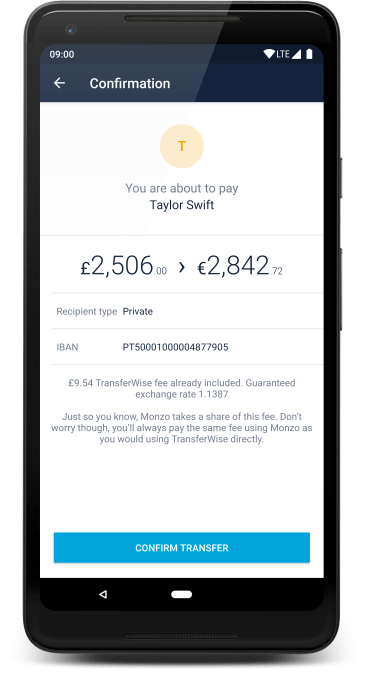

The TransferWise functionality will start rolling out to Monzo users as of today and will let them send money from their current accounts to 18 of the most popular currencies, with “more being added in the near future”. The user experience will be near-identical to TransferWise’s own app, and will see transfers happen at claimed ‘mid-market’ rates in addition to TransferWise’s low and transparent fee. This means you’re told upfront exactly how much you’ll pay in fees and the amount you’ll receive in the exchanged currency.

The TransferWise functionality will start rolling out to Monzo users as of today and will let them send money from their current accounts to 18 of the most popular currencies, with “more being added in the near future”. The user experience will be near-identical to TransferWise’s own app, and will see transfers happen at claimed ‘mid-market’ rates in addition to TransferWise’s low and transparent fee. This means you’re told upfront exactly how much you’ll pay in fees and the amount you’ll receive in the exchanged currency.